|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

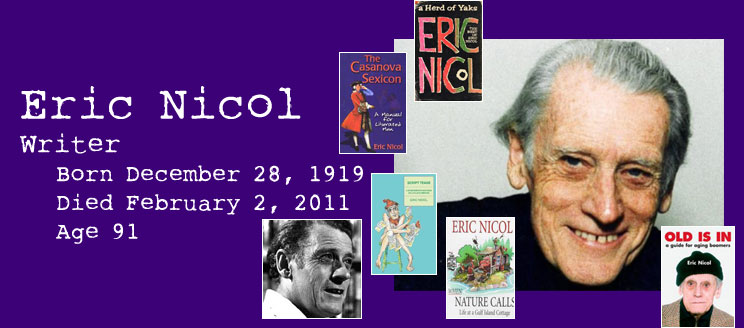

I may make a rule that if you get a solo, you write the update. Charlene, however, volunteered, as she often does, for her first hit of the year. She's terrific at this. * * * "Legendary." The Canadian media keeps using that word. It does not mean what they think it means — which seems to be "famous enough to get a CP obit." So when David Carrigg of the Vancouver Province used the word to describe Eric Nicol, I'm sure many younger readers yawned and turned the page — which is unfortunate, because in this case Carrigg used exactly the right word. Eric Nicol was simply one of the funniest writers in the English language. Whether he was writing about history (one of his favorite subjects), politics (another), sex (ditto), or simply everyday life, he could always make you laugh and think. His humour wasn't rough, but it was sharp, topical, and often more to the point than a casual reader would realize. He skewers the RCMP in "Dickens of the Mounted" (btw, buy this book), family life in "In Darkest Domestica," and his own country in "Canada Cancelled for Lack of Interest," but he slides the stiletto in so smoothly that you hardly notice. Eric Nicol won three Stephen Leacock medals, was appointed to the Order of Canada, and even had a mangled version of one of his plays flop on Broadway, but he was probably most pleased to receive the BC Gas Lifetime Achievement Award. (I know I would be.) He died at the age of 91, leaving behind him upwards of forty books, 6,000 columns for the Vancouver Province, three children, and one lucky deadpooler — me — who gets two points, plus five for the solo. Total: 7. — Charlene |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

DDT (the winner of the 2011 AO Deadpool) volunteered for Neil Young, and did a terrific update. Hulka sent along something with his update for Charlie Louvin, and I couldn't resist pairing the two. I like the idea of twinning the updates, because the only reason DDT had Neil Young is that we made him separate some Siamese twins. * * * Neil Young lent his fiery guitar skills and wheezy, strangulated tenor voice to several of rock music's most era-defining acts, from the pioneering country-rock fusion of Buffalo Springfield to the barbershop folk harmonies of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. His work with Crazy Horse anticipated the "alternative" sound of the 1990s, and modern rock mainstays like Pearl Jam frequently acknowledged his enduring influence. His musical interests ranged far enough afield that his record label once sued him for not sounding enough like himself. He was ... What? Really? Oh, dammit. Alright. — Hulka * * * Neil Young was an English footballer who for many years played for his boyhood idols, Manchester City. Today Manchester City is owned by Arabian oil billionaires. They are, on paper, the richest football club in the world and pay their playing staff accordingly stupendous wages. They employ an international array of expensive stars from far-flung places like Argentina, Brazil and Togo, and it's rare that any local talent ever gets to feature for their first team. Neil Young came from a different, bygone era. He was so local that he could see Manchester's stadium from his bedroom window. As the British and Americans continue to remain blissfully ignorant of each other's favourite sports (cricket, anyone?) and it hardly seems worth listing the highlights of Young's career here, suffice to say that he was an integral part of his club's finest hours. For those interested enough to learn more, here's a lovely video tribute to him. Young earned an insignificant wage and retired into obscurity, spending the remainder of his working life in menial jobs. There was little glamour and glitz in his life, and this is perhaps why his loss is so keenly felt by fans of Manchester City: He was one of them. At the very end of 2010, Neil Young announced that he was terminally ill, and deadpoolers everywhere who hadn't already submitted their teams fell on him like a pack of wolves. A few weeks into 2011, he succumbed to the cancer he had battled for five years. There was no fuss, right to the end. Manchester City held a minute's silence for him before a recent Saturday match. It would be nice to think that today's players, who earned more in that minute than Neil Young used to earn in a week, used the time to ponder their own good fortune. No doubt they'd be thankful, knowing that they will never need to seek employment in a supermarket to make ends meet when their own short careers end. — DDT

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Peggy Rea's ancestors arrived in California in 1849, part of the swarm of miner forty-niners looking for gold. If they ever found any, it wasn't enough to make a difference, but they did settle down and raise babies who raised babies, and eventually we get to Jack and Ruth Rea, who produced Peggy in 1921. They sent Peggy to UCLA, but Peggy decided to leave there and attend secretarial school. Maybe she wanted to learn as much as she could about one of the few trades open to women before World War II, or maybe she had a master plan. Peggy found work at M-G-M and, later, at CBS Radio, where she worked on the same floor as a couple of writers named Bob Carroll Jr. and Madelyn Pugh Davis. Carroll and Davis wrote for a show called My Favorite Husband, which starred Lucille Ball. Through all this, Peggy typed letters by day and, by night, went on stage in small theater productions. Somebody noticed, and in 1947 Peggy wound up in a revival of A Streetcar Named Desire. Anthony Quinn starred as Stanley. Peggy played Eunice, the nosy landlady who befriends poor, doomed Blanche. The production toured for two and a half years, and even played for a couple of weeks on Broadway in 1950. Peggy stuck around New York and landed another role, this time as the goddess Vulcania in the Cole Porter comedy Out of This World. It ran for five months. There was also a musical revue called Lend an Ear that paid the bills for a little while. Eventually, Peggy returned to California and got back into production, again at CBS. That was when I Love Lucy came along. I Love Lucy was pretty much the TV version of My Favorite Husband — Lucy does wacky shit, goes waaaah at the end, the whole bit — but I Love Lucy was a mega-hit, almost certainly because it also had Desi Arnaz, Lucy's actual husband. Bob Carroll Jr. and Madelyn Pugh Davis were still writing for Lucy (and, now, Desi), and they remembered Peggy. Peggy's first appearance on TV was as a member of Lucy's Wednesday Afternoon Fine Arts League in the fall of 1952. Ten episodes later, Lucy Ricardo gave birth to Little Ricky, and Peggy was cast as "Nurse Pushing Wheelchair" in the biggest thing that had been on TV up to that time. Peggy would do a couple more episodes of I Love Lucy before putting her acting career on hold and moving back into production. Peggy was the casting director for Have Gun, Will Travel, in which she cleverly cast herself in at least eight episodes from 1957 to 1963. She became familiar to viewers, though, when Red Skelton featured her in his highly rated variety series beginning in 1966. Peggy was often in The Silent Spot, a few minutes of pantomime that Red did at the end of nearly every show. Not many could hold a stage with Red Skelton, but Peggy did, and people noticed. Peggy worked steadily after that, on everything from The Man from U.N.C.L.E. to The Patty Duke Show, where they misspelled her name in the credits. Then, all of a sudden, it's 1971 and Peggy's on an episode of All in the Family, which had an audience of roughly three billion back then. The episode is the highly anticipated second-season opener. It's about Archie's cousin Oscar, who has dropped dead at the Bunkers' house, and they're having a wake there for him. Peggy enters and bellows the line, "I'm Cousin Bertha, Wilbur's daughter from Ozone Park!" and everybody laughs and laughs, and the world suddenly turns a little brighter. Peggy worked all the time after that. Peggy was in a few movies, most notably George Pal's 1964 film The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao, Gordon Parks' 1969 drama The Learning Tree, and In Country, a 1989 drama about the continuing problems of Vietnam veterans, but people probably know Peggy best for her working as a continuing character in several TV series. First there was The Waltons, a folksy thing about good-hearted people who live in the mountains but act like they live in the L.A. suburbs, except there's no traffic. Peggy guested in a 1978 episode and then came back the following year as a different character, Cousin Rose Burton, a relative of Mama Olivia Walton. Peggy did 37 episodes during the series' final two seasons. During and following her stint on The Waltons, Peggy appeared as Lulu Hogg on The Dukes of Hazzard, which was sort of the Bizarro World version of The Waltons. Lulu was Boss Hogg's wife. (Who was Boss Hogg? I don't really care, and neither should you. It's probably in Wikipedia.) Peggy did only 18 episodes of The Dukes of Hazzard between 1979 and 1985, but they must have been memorable because, inevitably, when people talked about Peggy following her death, The Dukes of Hazzard was usually the first or second thing they mentioned. Peggy also played Suzanne Somers' mother during the first year of the 1991-98 series Step by Step, and then went on to play Brett Butler's mother-in-law in Grace Under Fire, which ran from 1993 to 1998. Peggy appeared in about every other episode. As the 21st century dawned, Peggy took it a little easier, but she remained deeply connected to the L.A. acting community that she had helped found. She also made an occasional appearance at gatherings of fans of The Waltons and The Dukes of Hazzard, where you could always get a signature and a picture of that smile. Beth & Teresa get five points for the hit and five for the solo. Total: 10. — Brad |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

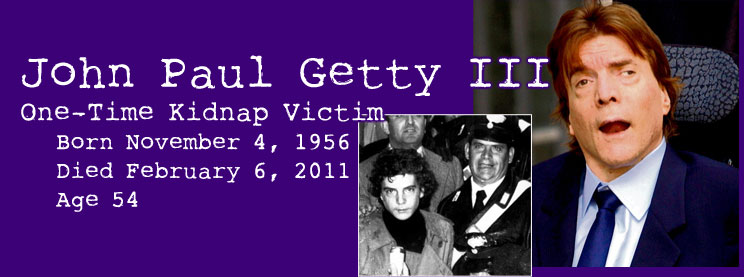

A Bill Schenley special. * * * You know how you think that if you would win the lottery — the Powerball — all of your troubles would disappear? Everything would just be peachy-keen. Pay off the overdue bills, get that new car you deserve, trade in the wife with an ass the size of Montana... Never works out that way, does it? For example, look at John Paul Getty III, grandson to one of the richest men in the world — his namesake, J. Paul Getty Sr. J. Paul Getty III was born with a winning Powerball ticket in his mouth, and then spent the rest of his miserable life proving to all that money will not buy anyone happiness, no matter how much you squander on heroin, cocaine and alcohol. Getty III, an obnoxious, spoiled, entitled brat until he was kidnapped at age 16, has died at 54, minus one ear and after almost thirty years in diapers. In 1981, after binging on Valium, heroin, methadone and alcohol, Getty suffered a stroke that left him almost blind and a quadriplegic. Still, Getty III came by his demons honestly; his grandfather was as cruel as he was stingy. Getty Sr. initially refused to pay his grandson's kidnappers any ransom until he was able to renegotiate the number. Then Getty Sr. demanded that his son, Getty II, reimburse him for the ransom at a rate of 4%. Senior installed pay phones in his Santa Monica mansion just in case one or two or twelve or thirteen of his guests wanted to make a call. Getty II was a notorious heroin addict and whoremonger who, after inheriting his dad's money, refused to pay for Getty III's care after the stroke. By the way, Getty II's second wife, Talitha Pol, died of a heroin overdose. Kathi also comes by her Getty III solo honestly. She pushed his wheelchair around for the last three years. Wiped his drool and changed his diapers. For her patience, she gets a whopping 14 points for the hit, this charming gift thoughtfully donated by this guy, and 5 more points for the solo. Total: 19. — Bill Schenley |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

You ever wonder what to do with all those filthy Indians moving to America? And I don't mean Cochise, I'm talking about those curry-eatin', vermin-lovin', unwashed-turbanized, Nehru-jacket-wearing bastards from India; you know, the ones who are better educated and more motivated than the latest generation of shiftless, fucktard Americans ... Yeah, those guys. The ones who are not only getting American jobs outsourced to them on the other side of the world ... but right here in the Red and Blue states they are taking decent white people's jobs because they have no idea what a union is and they're better at the maths and they actually work hard. Yes. Those fuckers ... The ones who don't wear socks and are on a first-name basis with Black Death-carrying New Delhi rats. Well, here's the thing, the late Josefa Iloilo, who was the president of Fiji, and who has died at 90, he knew what to do with people who were not just like him. He knew what to do when someone of a different color took over as president of his country. He done took a baseball bat to the ass of Mahendra Chaudhry, that damned furriner from India. Held him hostage for a few months, threw democracy out the window, suspended Fiji's constitution, named his pal Commodore Bainimarama as Prime Minister and, thankfully, outlawed green curry in Fiji. None of that pansy birther bullshit for Iloilo. And one more thing, he was a Methodist. DDT, who was not a favorite of Iloilo because he (DDT) once spent a steamy, degenerate, leather-themed weekend with some Indian whore (Agnes Bojaxhiu) in a Motel 6 on one of Fiji's 300 islands, gets two points for disposing of Iloilo, and another five for doing it all alone. Total: 7. — Bill Schenley |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

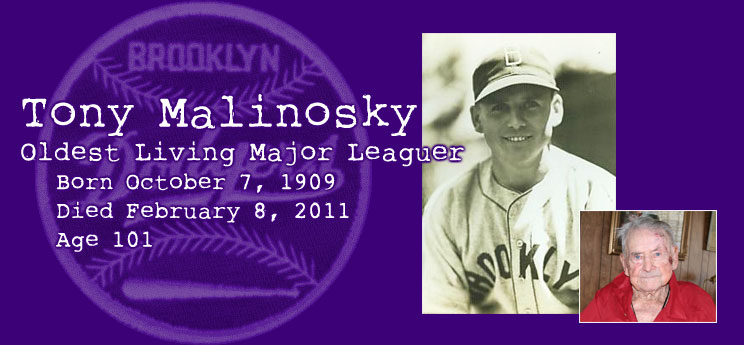

Tony Malinosky, who was the oldest living major league baseball player when he died at 101, was much more than those 35 games he played in for the 1937 Brooklyn Dodgers. After a knee injury ended his professional baseball career, Malinosky served in the United States Army, and he fought in the Battle of the Bulge. After World War II, Malinosky worked for a company that built military airplanes. He had been married to his wife, Vi, for 64 years ... And he once had his ass handed to him by a former classmate at Whittier College. He and his wife loved to travel around the country, and at one time they found themselves in St. Paul, Minnesota, at the same time Richard Nixon was there. The Malinoskys managed to get through Nixon's security long enough to say hello. Actually it was, "Hi, Dick." Tricky Dick let him know that he was the President of the United States and that he should be addressed accordingly. Malinosky didn't get a lot of hits as a Dodger, but he did hit a few pretty good pitchers, like Dizzy Dean and Carl Hubbell, and when Tony played for the Dodgers they didn't bleed Dodger Blue but Kelly Green. And while playing for the 1933 Tulsa Oilers, Malinosky was teammates with Howdy Groskloss, who was the oldest living major leaguer from July 30, 2005 until July 15, 2006. Malinosky said the greatest day of his life took place in 2009 when the Los Angeles Dodgers honored him at Chavez Ravine. Probably a good thing his wife had preceded him in death ... Allen Kirshner (who prays for shattered geriatric hips) and Constant Irritant (who should be ashamed for picking on a veteran) each gets one point for the hit and an additional three bonus points for the duet. Total: 4. — Bill Schenley |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

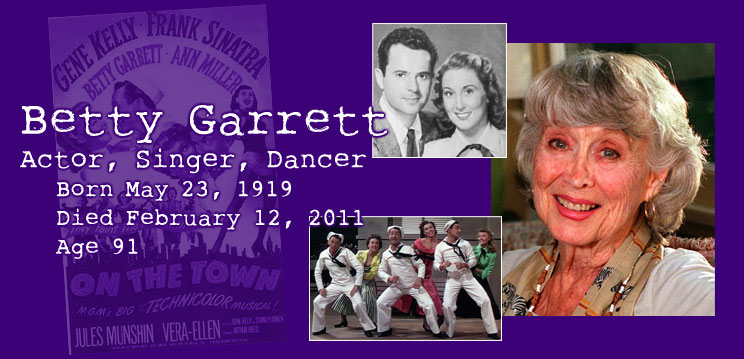

Betty Garrett began to find her way when she and her mother moved to New York in 1936. Betty studied at the Neighborhood Playhouse with teachers like Martha Graham and Sandy Meisner. It must have been intense. During the summer, she worked at hotels in the Catskills north of the city, the famed Borscht Belt. Despite all the tummeling with Danny Kaye and Imogene Coca at places like Grossinger's, Betty thought of herself as a dramatic actress, so in 1938 she hooked up with Orson Welles' Mercury Theater. She danced at Carnegie Hall, sang at the Village Vanguard, and wound up performing with the American Youth Theatre. That was around the time she joined the Communist Party. Betty's first Broadway gig was in 1942's wartime revue Of V We Sing, which ran only a couple of months, but more jobs followed: another wartime revue, Let Freedom Sing; Cole Porter's Something for the Boys (yes, yes, more wartime stuff); Jackpot, a flop; and Call Me Mister. That one got Betty a contract with M-G-M. She began working there at the beginning of 1947, making musicals, one right after the other. One of them was On the Town. On the Town is great because it's about sailors on liberty in New York, and it was shot in New York, on location. That had not been tried before, but Gene Kelly wanted it that way. It's one of the great musicals, and Betty's a hoot as Brunhilde the cab driver, who winds up in love (or some ersatz wartime equivalent thereof) with Frank Sinatra. But the real love of Betty's life was actor Larry Parks, who's best remembered today for his Oscar-nominated performance as Al Jolson in two film biographies. Larry was the love of Betty's life. In 1944, Betty performed in a show produced by Larry at the Actor's Lab in Hollywood. They got married four months later. Larry had been a Communist for a few years by then, but he and Betty appear to have quit the Party together around the time of their wedding. That didn't matter to the House Un-American Activities Committee, which in 1951 called Larry to testify about his Communist past. The scandal derailed his career. HUAC would have called Betty, too, but she dodged the bullet because she was nine months pregnant with her son Andrew and likely would have come off as too sympathetic a witness. However, roles for them both were suddenly few and far between. Columbia dumped Larry and M-G-M let Betty go. They tried touring with a live musical act and did well for a while, but eventually Larry turned back to construction work. He built houses on spec but, instead of selling them when they were finished, he decided to become a landlord and rent them himself. Larry wound up doing well, and if there's some irony attached to the notion of a former Communist becoming a prosperous landlord ... well, ain't that America. Eventually, the blacklist faded away, and Betty wound up doing a lot of television from the mid-'70s on. She may be best remembered for her series work — first as the Bunkers' neighbor Irene Lorenzo in later episodes of All in the Family, and then as Laverne's eventual stepmother Edna Babish in Laverne & Shirley. Larry and Betty remained married until Larry died suddenly in 1975, during Betty's run on All in the Family. She never remarried. Betty worked and taught until the very end. Look all you want, all over the net, and you will not find an unkind word about her. Still active and still pursuing her craft, Betty died at the age of 91, admitted to the hospital on Friday and gone on Saturday. She had long outlived all the thoroughly forgotten bastards who had tried to tear her and Larry down, and she had carried on with style and class. A fine ending, and the best revenge. Beth & Teresa, Busgal, Jazz Vulture, Tim J and Undertaker get two points each for the hit. — Brad |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

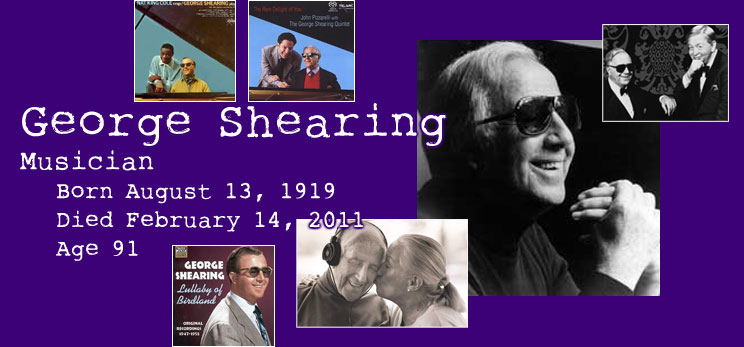

Say George Shearing and you think "blind jazz pianist." But there's a bit more. For one thing, he thought of himself as a pianist who happened to play jazz. I thought I knew enough about jazz that I would know that George Shearing wrote "Lullaby of Birdland." But I didn't. Not until I read the obits. (Nor did I realize he lived in Manhattan and Lee, Mass. Did he eat at Joe's Diner? If so, was he as inspired as Rockwell?) Back to "Birdland." One of my favorites. I can hear Sarah Vaughan singing it. And so can you! 'Lullaby of Birdland' by Sarah Vaughan Does it get any better than this? Remember the old days when instead of punching "repeat" you got up from the floor and picked up the tone arm/needle and put it back a cut? Maybe that's why we were thinner back then. I can remember doing this a lot with this version. Shearing got tired of recording it, but not of collecting the royalties. And he was amused at its comparative fame. He would introduce the song by saying, "Two hundred ninety-nine enjoyed a bumpy ride from relative obscurity to total oblivion," he said. "Here is the other one." George Shearing has died at 91. Wendy has gotten the solo. She gets 2 points for the hit and 5 for the solo. Pretty nice hit there, Wendy. Sorry I took so long to get you out of the cellar. Here's an anecdote I love: One afternoon, at rush hour, Shearing was waiting at a busy intersection for someone to take him across the street when another blind man tapped him on the shoulder and asked if Shearing would mind helping him to get across. "What could I do?" said Shearing afterward. "I took him across, and it was the biggest thrill of my life." — Amelia |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

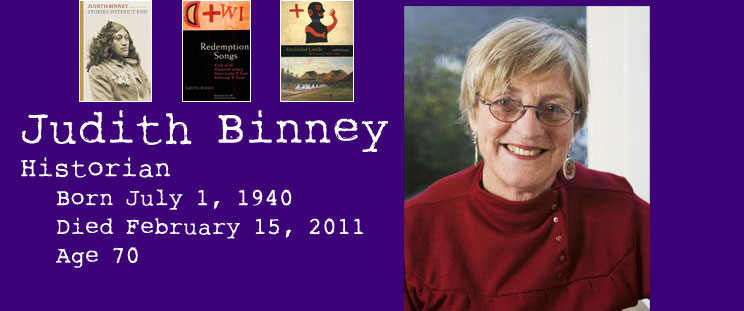

In this lovely age we're living in, where teachers are held in such low esteem (well, as compared to salt-of-the-earth investment bankers) and libraries have now been deemed expendable, it's a pleasure to report that Dame Judith Binney was an academic who brought Maori history to life for decades of students, and a scholar whose many books drew on oral histories, communal memories and the collections of the National Library of New Zealand, of which she was a Guardian, which I assume means board member. Binney recovered the "lost history" of Te Urewera, the Ngai Tuhoe people. In particular, her work documented the first hundred years of Te Rohe Potae o Te Urewara — the "encircled lands" of the Urewera — following European contact. Encircled Lands won the 2010 Book of the Year Award in the NZ Post Book Awards. It was just one of many awards for her scholarship. Binney's groundbreaking work and passion for teaching inspired thousands who learned from her lectures and her books. Tuhoe honored her with the title of endearment "Te Tomairangi o te aroha (Tears of love)." Hard to imagine them doing that for an investment banker. Jazz Vulture and Sarndra, from two different walks of life, get together for the duet on the 70-year-old Binney. They get 8 for the hit and 3 for the duet. Total: 11. — Amelia |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

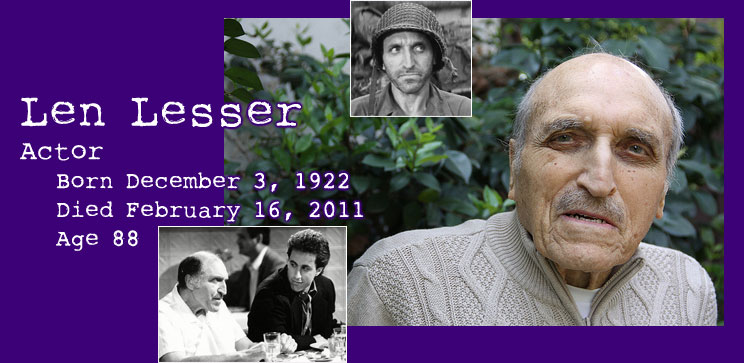

It's amazing how often you hear it. I heard it today in a Verizon store, a woman loudly complaining (read: hard of hearing) that the volume wasn't working on her new phone. She said it: This is like a Seinfeld episode. Maybe it's about nothing. Maybe it's about babka. Maybe it's about a sliding entrance into a room. Whatever it's about, it's character actors like Len Lesser that make it like a Seinfeld episode. With Uncle Leo, it was the greeting. "Jerry! Hello!" — loud, obnoxious, and demanding reciprocation. No matter the scene. No matter the embarrassment. "You still say hello." This is what made it a Seinfeld episode. This is what makes life a Seinfeld episode. Len Lesser, as a character actor, cast a wide net. He had bit parts in dozens of feature films and television (usually) sitcoms. Did you know his character name in Papillon? Get Smart? The Monkees? The Outer Limits? The Outlaw Josey Wales? Nah, you didn't. But from 1991 'til the end of his days, if you saw him in the street, you yelled out "Uncle Leo!!" Everyone did. He probably had to reciprocate. It's only right. And all this fame for a sum total of fifteen episodes. Such is the power of television. Such is the power of a Seinfeld episode. Kixco gets the splendid solo here while we all say "Goodbye, Uncle Leo." She gets 5 for the hit and 5 for the solo. Total: 10. — Amelia |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

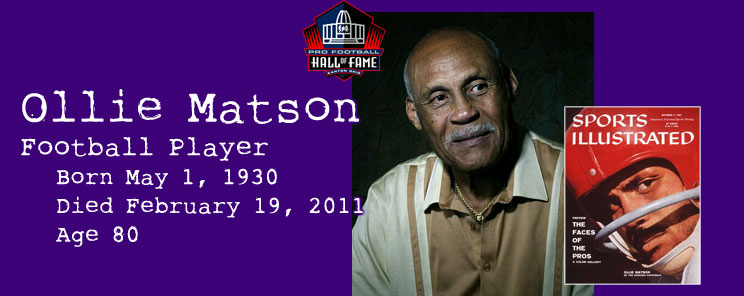

Ollie Matson was a former NFL running back who seemingly had outlived his fame. He wasn't just another dead one-time football player. He was one of a handful who is considered one of the greatest to ever play the gridiron game. Playing for the Chicago Cardinals, the Los Angeles Rams (in 1959, the Rams traded a record nine players to the Cardinals for Matson), the Detroit Lions and the Philadelphia Eagles, Matson was a halfback, fullback, flanker, quarterback, special teams (kick/punt returns) and a defensive back. In 1961, the Heisman Trophy was won by Ernie Davis of Syracuse. Davis, the Elmira Express, became the first Black man to win the coveted trophy. However, the Heisman arguably should have been won by an African-American at least ten years earlier. Matson, who played college football at the University of San Francisco, led the nation in rushing yardage and in touchdowns in 1951. Despite USF's undefeated season (9-0), they were not invited to any bowl games. The Gator, the Sugar and the Orange Bowls did not invite teams that held roster spots for Negroes. Of the 987 registered Heisman electors, only 95 gave Matson a vote — and only six gave him a first-place vote. USF's motto after the 1951 season was "Unbeaten, Untied, and Uninvited." Ollie Matson finished 9th in the Heisman voting behind future NFL stars like Hank Lauricella [1], John Bright [2], John Karras [3], Larry Isabell [4] and the winner, Princeton's Dick Kazmaier [5]. Babe Parilli, Bill McColl and Hugh McElhenny, who also finished ahead of Matson (3rd, 4th and 8th, respectively), all had significant NFL careers. Also, at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Ollie Matson won a bronze medal in the 400-meter dash and a silver with the 4x400-meter relay team. Yes, Ollie Matson was seemingly forgotten — except by the AO Deadpool's Deepstblu, who rushes for ten points on his first hit of the year. Five for the hit and another five for the solo. Total: 10. [1] Played in 11 games in the NFL. — Bill Schenley |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

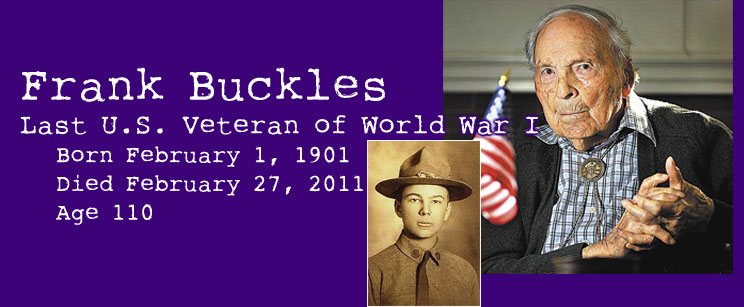

I know you prefer it when we write them, but this piece from the Washington Post was so moving, I wanted to share it with you. Allen Kirshner, Buford, Deceased Hose, Erik and Undertaker get the one point. — Amelia * * *

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

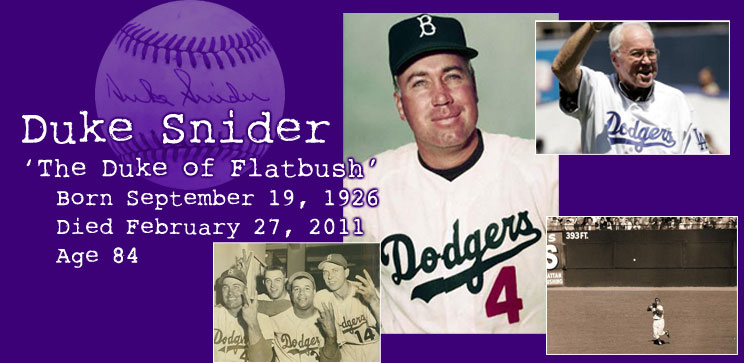

Duke Snider, one of Roger Kahn's Boys of Summer, has died at 84. Before I was a Yankee fan, I was a Brooklyn Dodger fan, or so I thought. My mother was a Dodger fanatic, and she took me to my first major league baseball game, at Ebbets Field. Before I knew Yogi Berra was the Yankees' catcher, I knew Campy was the Dodgers' backstop. Before I could recite the names of the Yankee infielders (Bill Skowron, Billy Martin, Andy Carey and Gil McDougald) I knew their counterparts in Brooklyn: Gil Hodges at first, Junior Gilliam at second base, Jackie Robinson in the hot corner, Peewee in the middle. I knew Bauer, Ellie and Mantle ... but first I knew Furillo, Sandy Amoros and the Duke of Flatbush. Duke Snider, the center fielder for the Dodgers at the first major league baseball game I ever saw — to me, that has always been really cool. Because the Duke was a part of New York baseball at its best. My mother must have had a dozen Duke Snider autographs. She'd wait for him to leave the ballpark, drag me along, and accost him, with a few hundred other Bum fans, and ask him to sign a program ... for her son, who was six and didn't know what an autograph was. She also dragged me to the Polo Grounds for the same ruse. Fortunately, for me, the following year I saw the Yankees play the Indians at Municipal, and I began talking non-stop about another center fielder from New York. So there would be no more Dodger games for me until I moved to Los Angeles in 1968. But I always liked Duke Snider. Chipmunk Roasting drove in five runs for herself with the death of the Silver Fox, and because it was a solo hit, she gets an additional five bonus points. Apparently she doesn't bleed Dodger Blue. Total: 10. — Bill Schenley |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

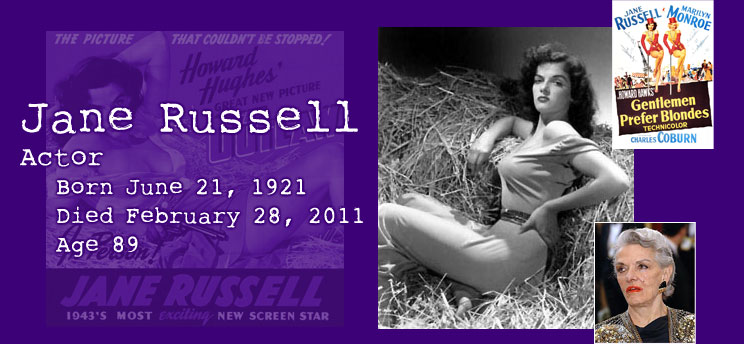

You know what the best thing is? When you get an update unsolicited in the mail. It's almost like getting money. (But not quite.) We should all thank new player Brave Last Dave for this marvelous recap of Jane Russell's life. * * * Jane Russell began her career as a pair of stunt tits. Howard Hughes, who produced a lot of movies back in the 1930s and 1940s, decided to direct his second (and last) movie in 1943, The Outlaw. In 1930, he directed Hell's Angels, a movie about flying, a topic near and dear to his heart. The Outlaw was a stale Western melodrama about an already over-exposed character, Billy the Kid, starring an unknown actor named Jack Beutel, who turned out to have a serious charisma deficiency. No matter, thought Hughes. He decided that what the public really wanted was big tits, and almost all the publicity for the film was pictures of Jane Russell, featuring her breasts from nearly every possible angle. She wasn't an actress or even a model then. It's obvious she is supposed to be looking sultry in the publicity stills, but she comes off as mean or bored or both. She got better as time went on. It helped that she was cast opposite better actors like Bob Hope (Paleface and Son of Paleface) and Robert Mitchum (His Kind of Woman and Macao), and it helped that they let her sing instead of just standing around showing off her chest. Besides the publicity stills from The Outlaw, her best-known film work is in the iconic glamour musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes with Marilyn Monroe in 1953, with the great duet "Two Little Girls from Little Rock." It's the rare fabulous babe actress of that era in Hollywood who remained a star once she got past 35, and much of Russell's later career was on TV in supporting roles. Baby boomers may remember her best as a spokeswoman for Playtex's Cross Your Heart bra, which was the "18 hour bra" she said was made for "us full-figured gals." The stunt tits had grown into mature and believable tits. She married three times. Her politics were Christian, right-wing and pro-life. In 1955, she started the World Adoption International Fund (WAIF), which encouraged Americans to adopt children from other nations, so she was way ahead of the curve on that front, and she put her money where her mouth was. Good for her. — Brave Last Dave

|

||||||||||||||